Stanley Schtinter, Last Movies (A limited Tenement & purge.xxx hardback edition.)

£35.00

With a Foreword / Programme Notes

from Erika Balsom;

an ‘Intermission’ from Bill Drummond,

& an afterword by Nicole Brenez ...

Tenement Press / purge.xxx

ISBN: 978-1-7393851-6-3

230pp [Approx.] / 140 x 216mm

Edited by Dominic Jaeckle

Designed and typeset by Traven T. Croves

Forthcoming 05.11.23;

preorder a copy direct from Tenement.

•

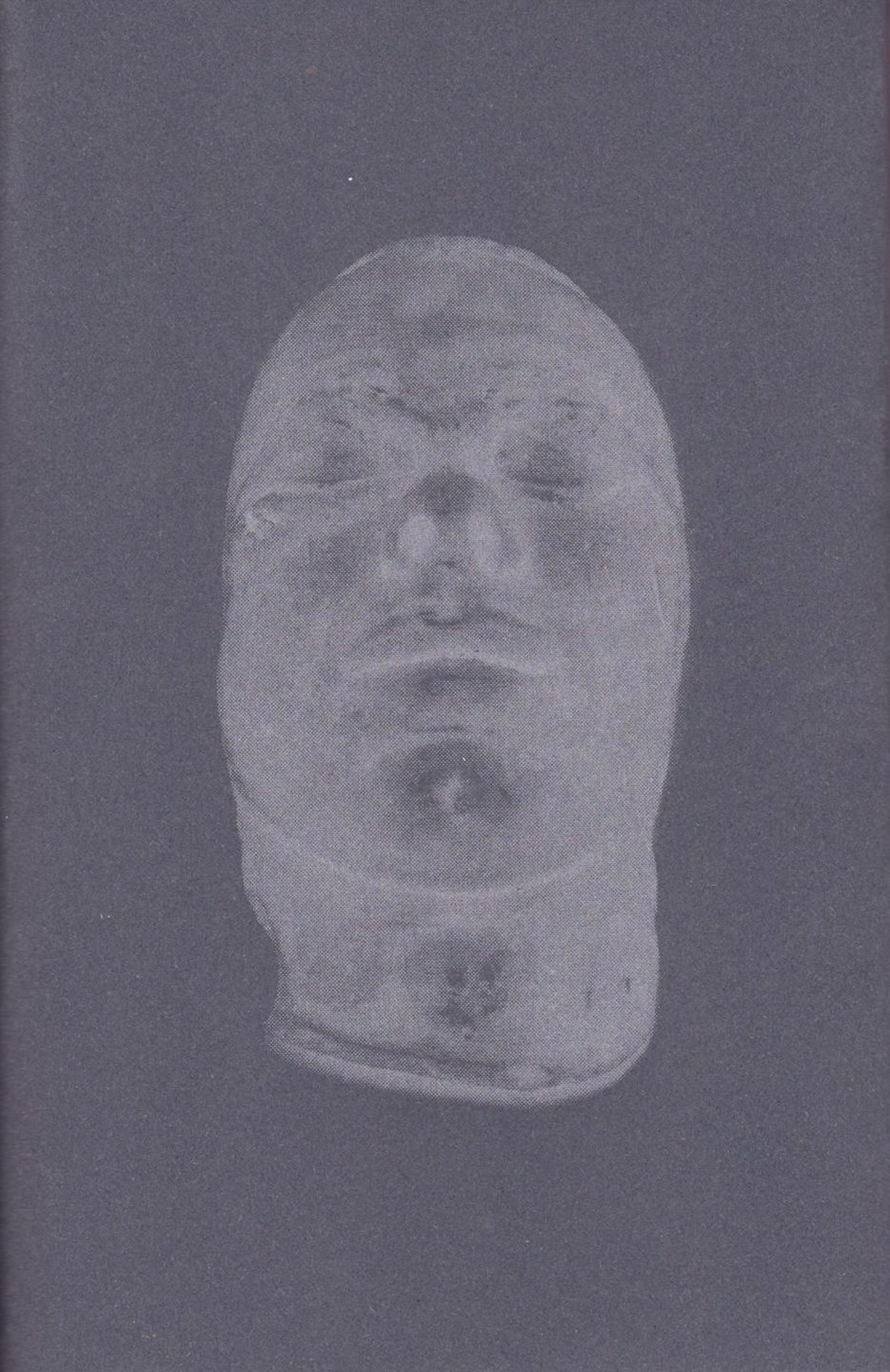

A special, limited edition hardback edition of Schtinter’s debut collection, carrying a “glow-in-the-dark” iteration of John Dillinger's death mask on its cover. Available November through New Year’s Day, 2024. Order from purge.xxx to receive an accompanying cassette carrying an unabridged reading of Last Movies by the author.

•

Very strange, and deeply thought-provoking.

Laura Mulvey

A durational artwork, moving-image experience, and parallel publication, Schtinter’s Last Movies—the tenth “Yellowjacket” from Tenement Press—remaps the century of cinema according to the final films as watched by a selection of its icons ...

•

What is a society that values nothing more than survival?

Giorgio Agamben

The cinema can kill, just like anything else.

Louis Malle

A furnace of facts in our age of entirety;

a compendium of endings from the artist ...

Stanley Schtinter’s debut collection, Last Movies, is an extensive and exhaustive research project. A holy book of celluloid spiritualism and old canards that—questioning and reconfiguring common knowledge—recasts the historic column inches of cinema’s mythological hearsay into a thousand-yard stare of a book. An excoriation of the twentieth century (and our dance into the twenty-first), Last Movies antagonises the possibility of survival in an age of extremity and extinction, only to underline the degree of accident involved in a culture’s relationship with posterity.

Here, we’ve a book in which Manhattan Melodrama, directed by W.S. van Dyke and George Cukor, is seen by American gangster John Dillinger, only for him to be gunned down by federal agents upon leaving the cinema. In which George Cukor watched The Graduate, and dies thereafter. In which Bette Davis—given her break by Cukor—watches herself in Waterloo Bridge (the 1940 remake Cukor had been meant to direct), before travelling to France and failing to make it back to Hollywood. In which Rainer Werner Fassbinder watches Bette Davis in Michael Curtiz’s 20,000 Years in Sing Sing, and suffers the stroke that kills him. In which John F. Kennedy watches From Russia with Love at a private ‘casa-blanca’ screening prior to the presidential motorcade reaching Dealey Plaza; in which Burt Topper’s War is Hell exists only in a fifteen-minute cut, considering this is as much as Lee Harvey Oswald would have seen at the Texas Theatre in the wake of JFK’s killing.

Like Hermione Lee “at the movies,” and redolent of the works of Kenneth Anger, Schtinter’s Last Movies is enamoured by the ludicrousness of a swan song that lingers on in a world still trying to sing. Rather than a book dedicated to the effects of cinema on society, this is a collection of writings predicated by a dedication to cinema. Last Movies is a love letter to those that’ve lived (and died) amidst the patina and glow of cinema’s counterpoint to life (as lived) via a haphazard index of twenty-eight of its notable audience members.

This edition also includes programme notes (from a marathon screening), ‘Towards the Last Movies’ by Erika Balsom, an afterword / last word(s) from Nicole Brenez, & an intermission from Bill Drummond.

•

See here for further word on this title.

•

Last Movies brings together its selections by the force of an external event, one which bears not on the films themselves but on little-known details of their exhibition histories, and then orders them not according to any curatorial vision but by date of disappearance. It abandons all those calcified criteria most frequently used to organise cinema programmes: period, nation, genre, director, star, theme. Nothing internal to these films motivates their inclusion, their “quality” least of all. Although Schtinter can choose a death to research, the title to be shown is dictated by history. This is all to say that Last Movies embraces chance, an avant-garde strategy its orchestrator has been known to marshal in previous undertakings.

And so it should be for a programme about death. The tenacity of the “life review” flashback as a trope in fiction films could be attributed to the fact that people who have had near-death experiences claim to have encountered the phenomenon. It is more likely that this convention endures because it satisfies a reassuring fantasy: that life will ultimately attain coherence. The fantasy of that “last movie” is undone by the reality of Schtinter’s Last Movies. They are often random and in large part unchosen; they throw significance into crisis and demand acquiescence to externality. They are, in other words, like death itself.

Erika Balsom

The more details Schtinter’s Last Movies uncovers the more mysterious his project becomes. What are we meant to understand from learning that Franz Kafka’s last movie was The Kid (1921) by Charlie Chaplin? Or that Chaplin started casting it just one week after the death of his son Norman? Or that Norman’s tombstone read only ‘The Little Mouse’? Or that, after Chaplin himself died in 1977 (his last movie was Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon), his coffin was dug up from a Lausanne cemetery by two refugees and held to ransom? Perhaps it’s the freedom to speculate, the unanswerability of those questions, that is its own reward. Boldface names, lurid details, strange connection. Schtinter, always eager to deflate pomposity, likens his project to an “occult version of OK! magazine.” I myself can’t help wondering: what if we were to watch every movie as if it were our last?

Sukhdev Sandhu, Prospect

•

See here for notes on Schtinter's previous Tenement title, The Liberated Film Club. The second title in Tenement’s “Yellowjacket” series, a kunstkammer of a collection curated and collated by Schtinter that features works by John Akomfrah; Chloe Aridjis; Dennis Cooper; Laura Mulvey; Chris Petit; Mania Akbari; Elena Gorfinkel; Juliet Jacques; Ben Rivers; Dan Fox; Sean Price Williams; Adam Christensen; Stewart Home; Stephen Watts; Tony Grisoni; Gideon Koppel; Astra Taylor; Miranda Pennell; Gareth Evans; Adam Roberts; Tai Shani; Anna Thew; Xiaolu Guo; Andrea Luka Zimmerman; William Fowler; Athina Tsangari; John Rogers; Shama Khanna; Shezad Dawood; Damien Sanville; & Stanley (& Winstanley) Schtinter.

•

Praise for The Liberated Film Club ...

Schtinter runs with wolves.

Sukhdev Sandhu

There are more and more curators of experimental cinema, which is great; but unfortunately still few experimental curators. Stanley Schtinter offers us a fascinating and liberating example.

Nicole Brenez

•

Stanley Schtinter has been described by writer Iain Sinclair as ‘the last accredited activist, the last avant-garde.’ He recently presented the premiere of his “endless” video-work, The Lock-In, at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, and exhibited the work as a solo presentation at the Barbican Centre in London during July 2022 (reviewed for The Guardian by Jonathan Jones as ‘an epic film [...] spellbinding, Warholian’). From May 2021 until May 2022 he presented Important Books (or, Manifestos read by Children) at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. In 2021, he published the edited collection, The Liberated Film Club (Tenement Press). Schtinter is the artistic director of purge.xxx; an “anti-” record label (“anti-” everything) wherein he curates and publishes a catalogue of sound-works, soundtracks, and collaborations.

•

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna,

in die illa tremenda Quando cœli movendi sunt et terra

Dum veneris iudicare sæculum per ignem.

Tremens factus sum ego, et timeo,

dum discussio venerit, atque ventura ira

Quando cœli movendi sunt et terra.

Dies illa, dies iræ, calamitatis et miseriæ,

dies magna et amara valde

Dum veneris iudicare sæculum per ignem.

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine:

et lux perpetua luceat eis.